How deadly is Mars? Depends on the tardigrade

Thanks for tuning back into the BeX Files! Get your gardening tools and your spelunking gear, because today, we're going to try to inhabit Mars.

Mars is the main focal point of modern fantasies about human settlements in space—a planetary canvas that evokes classic frontier tropes due to its dusty desert landscape. Visions of green gardens growing in red regolith date back more than a century in science fiction, and have also become a thriving topic in modern astrobiology. But just how realistic is this dream?

For this week’s file, I wanted to spotlight two new studies that shed light on that juicy question.

The first study, published last week in the International Journal of Astrobiology, road-tests the kind of hardy lifeforms that might feasibly eke out a living on Mars—namely, tardigrades, also known as water bears or moss piglets.

These microscopic animals are the Rasputins of the natural world; you can try to kill them in all kinds of ingenious ways but they will simply refuse to expire. Tardigrades can survive boiling water, extreme dehydration, the vacuum of space, and getting shot out of a gun. They can stay put without food or water in a “tun state” for decades.

Heck, there could even be tunned-out tardigrades on the Moon, given that a spacecraft may have spilled a bunch of them there in 2019. It’s not much of a stretch to wonder if they could survive on Mars.

To that end, researchers led by Corien Bakermans of Penn State Altoona let a bunch of active tardigrades loose in Martian simulants, which are like faux-versions of red planet dirt (for an inside look at the extraterrestrial simulant industry, here’s my VICE feature from 2022).

“With future intended human missions to Mars, it is crucial to understand the potential habitability of martian regolith both to support plant growth and to mitigate accidental release of organisms from habitats,” the team said in their new study.

“We tested tardigrades, a group of valuable model organisms for animal development and survival of extreme conditions, as potential candidates for establishing functional soils on Mars,” the researchers added.

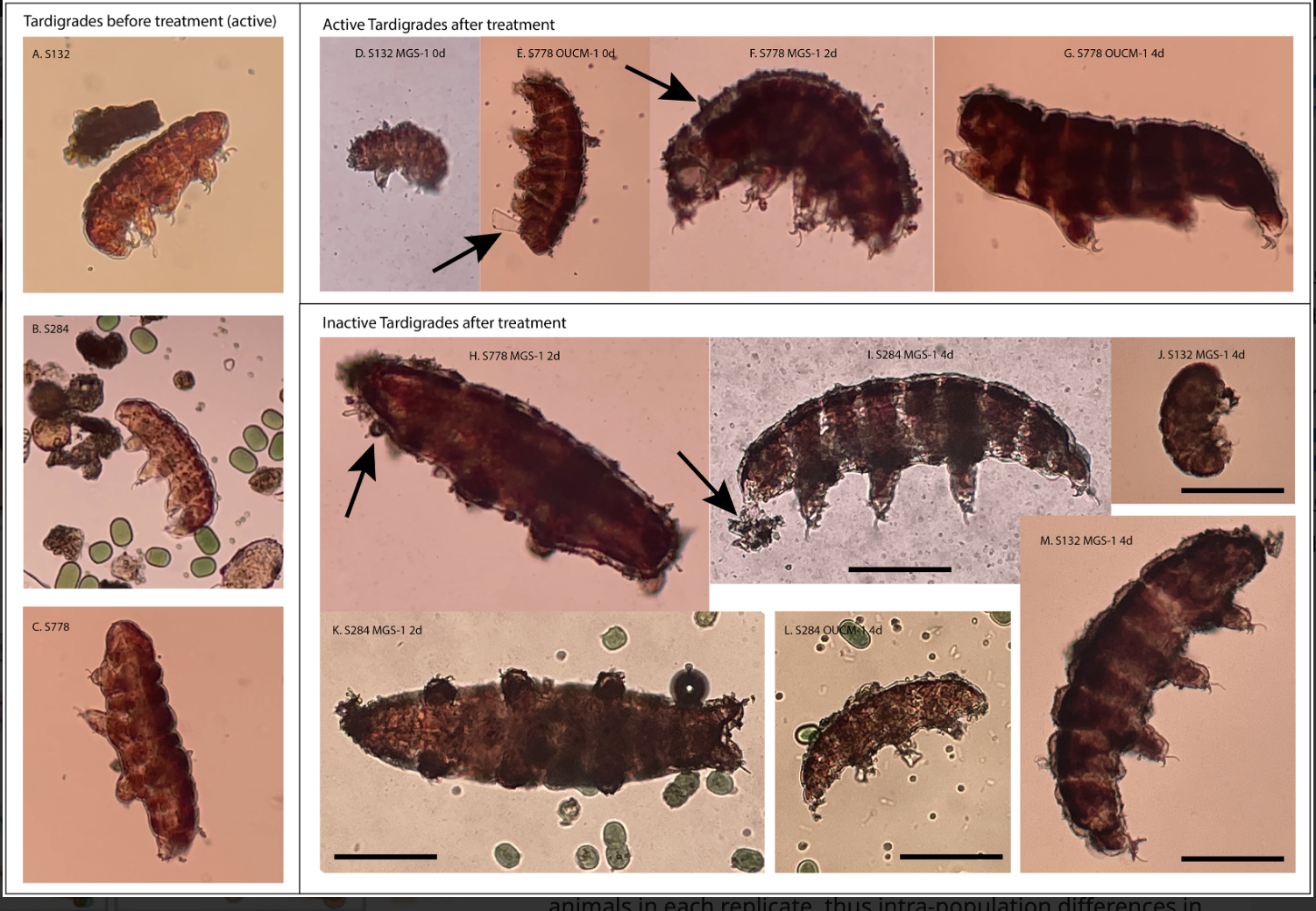

Two tardigrade species, Ramazzottius cf. varieornatus and Hypsibius exemplaris, were placed in two Martian simulants, MGS-1 and OUCM-1, while control groups were placed in regular earthly sand. The results revealed that even tardigrades—among Earth’s most legendary badasses—struggled to survive in this ersatz Martian soil for more than a few days.

“In the control, active tardigrades remained energetic,” the team said. “In MGS-1, most remaining active tardigrades were barely moving after two days…Inactive tardigrades did not visibly move within 10–15 seconds and were often bloated or slightly curled (Fig. 2); some inactive tardigrades were visibly disrupted or degraded and presumed to be dead.”

That said, the Ramazzottius tardigrades in OUCM-1 “were reasonably energetic at all time points,” suggesting that the animals might be able to survive under certain conditions similar to that particular simulant. Overall, the study is a reminder that even the most endurant Earthlings might not be able to tolerate a move to Mars.

“Our data are consistent with previous studies that have shown martian regolith simulants can be damaging to active cells,” the study concluded. “More testing is necessary to fully understand the potential habitability and dangers of martian regolith.”

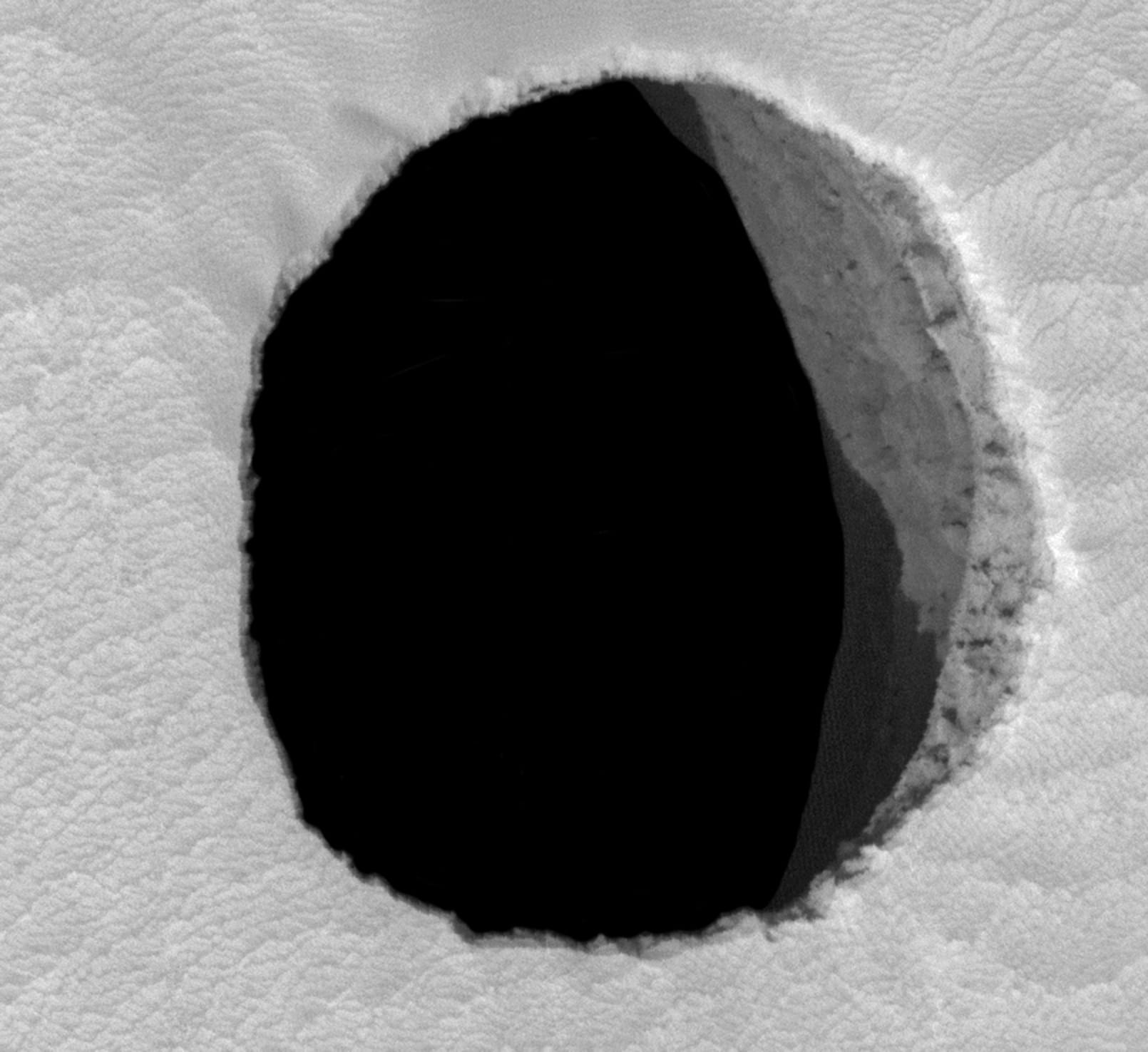

On the flip side, another study published this week from the same journal explores the tantalizing question of whether Martian subsurface caves—particularly dried-up lava tubes—might host alien life. These subterranean chambers are free from many of the dangers on the surface, such as damaging radiation and wild temperature fluctuations.

“The discovery of over 1,000 potential cave entrances on Mars, detected through data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s CTX and HiRISE cameras, underscores their significance for astrobiological investigations,” said researchers led by Federico Biagioli of the University of Tuscia. “Should Mars have ever hosted microbial life, caves would constitute some of the most promising environments in which to investigate extant or fossilized biosignatures.”

“The exploration of subsurface environments represents a new frontier in astrobiology, offering one of the most promising opportunities to answer the fundamental question of whether life exists or ever existed, beyond our planet,” the team concluded.

To sum up, our houseplants probably aren’t moving to Mars anytime soon, and neither are our toughest microscopic beasties. But Mars may still have some tricks hidden up those lava-tube sleeves. Who knows what might be waiting in the dark caverns that our robots haven’t yet reached?

Time to close up the file for this week! See you at the cosmic rest stop next Friday.